At the end of our Spring Fling discussion of Whitney, My Love by Judith McNaught, participants got to ask Scarlett questions. We did not have time to get to all of them! Scarlett generously offered to answer questions we didn’t have time to answer or get into as deeply as she wanted here on the blog. She plays FMK Red Herring Heroes Edition, gets into Fifty Shades, the influence of WML on her own works, and what we carry with us from romance of the ‘80s.

You can listen to the whole episode, and her answers to a few other questions, here.

Without further ado…

From Kate: I always thought Whitney should have ended up with Nicolas!

I totally get that!! Here’s where I’m at in my own journey: as a youth, I was completely in the tank for Clayton. (Listen, it was 1996, what can I say?!)

Upon rereading the book as a grown woman, if I had to do a f*ck/marry/kill on Whitney’s suitors...I’d want her to:

Sleep with Paul: It would be extremely perfunctory and he would not care about her pleasure, but he wouldn’t sexually assault her, at least.

Marry Nicky: They could go back to Paris where people appreciate Whitney rather than desire to crush her spirit. And I think Nicky is genuinely in love with her and intends his dominating air to be read as a flirtation to be playfully parried back...in contrast with Clayton’s menacing expressions of his rage-driven desire to conquer Whitney.

Kill Clayton, and fast: Because if she doesn’t, he will 100% kill her first.

From Leslee: Rape fantasy in is the fantasy of being violently violated. There are submissive masochists who genuinely have that fantasy. Most women, however, have ravishment fantasy, which is the concept of "this isn't my fault because he wants me so much, I can't resist" aka, what we were just discussing as far as not having to choose. I argue that the 2012 D/s fantasy is more of a misunderstanding of the D/s culture than in relation to either of these things.

I think we were talking about Fifty Shades of Grey when this came up. I haven’t read that book since it came out, so it’s not fresh in my mind, but as I remember it, I agree with you that I didn’t read the Anastasia/Christian dynamic precisely a rape fantasy. It seemed more like more of a loss of control fantasy to me, with a Chosen One trope?

I definitely agree with you that it is a problematic representation of the ethos of kink and BDSM, which are thoroughly and beautifully based in active consent and clear boundaries. The way that Christian forces his interest on Anastasia when she’s not looking for a D/s relationship...the way he offers up a written contract but doesn’t really care about her boundaries or enthusiasm in negotiating it... The many times he wears her down despite her explicit and implicit lack of interest in his kink… The way she keeps finding herself in the red room anyway… Yeah: NOT HOW TO DO IT.

I will say I don’t think the book was all bad. It helped build a cultural acceptance and de-stigmatization of kink, and an interest in practicing power exchange in vanilla relationships, even if it was a problematic representation of it.

I am also eternally grateful to the book for giving us “laters baby,” which I think is the pinnacle of comedy to use as an email signature. 😈

From Skyler : Scarlett can you see any way that the original WML whipping scene imprinted on you?

No way absolutely not and how dare you!!!!!!????

Oh, sorry, wait. I do vaguely recall writing a book about a whipping house with a scene where a guy humbly asks his beloved to wail on him with a riding crop? So, ok, YOU WIN THIS TIME, Skyler! ❤

From Carole: What I want to know is why? Why Judith McNaught wanted to write it and why people loved reading it?

To the first question, why McNaught wrote this: lucky me, that one’s a freebie. I have no idea!! You gotta ask Judith!

Next, as to why it’s beloved...I think there are a lot of genuinely delightful things about this book, even rereading it for my fifth or sixth time from a perspective of despising and feeling emotionally drained by reading it. Like:

The dialogue is sparkling and sharp and made me laugh out loud at least twenty times.

The relationship between Whitney and Clayton--if you take out the violent and abusive parts--is full of witty banter and palpable chemistry. (If you removed the dirty rotten abusive nature of every single part of their relationship, they’d be a great couple!)

The book is compulsively readable with a wide range of convincing and interesting characters.

Whitney is charming, hilarious, smart, sassy, defiant, brilliant at both surfing on ponies in britches and decimating dukes at chess... of the most memorable characters I have encountered in literature at large, let alone romance novels.

And, the book gorgeously nails or even originates many of the tropes that have become enshrined in romance…The sexy interlude with a tall, dark handsome man on the balcony outside the ballroom; the makeover/ugly duckling gets her revenge; the sexually charged competitions with the hero; the arranged marriage; the love triangle (quadrangle?)...I could go on and on.

But then there is the darker fantasy WML selling, and that is a way more complicated issue....which you also bring up, conveniently, in the next question!

From Carole: Why is this complicity so attractive? McNaught makes it justifiable as it ends in an HEA.

Forgive me for writing a memo on this, but I think it’s a really valuable and complicated question. (I tried to shorten my answer, but I have become too lazy to do complicated acts of writing if they do not produce novels I can sell on the Internet.)

Also please keep in mind that I am just a woman who dresses her cat in bowties and believes she has a psychic connection to her house, not a Scholar, so this is just my humble opinion.

But, ok:

First, there is the powerful archetype of male dominance and female submission as the basis of the traditional narrative of courtship in Western culture. And this narrative reflects centuries of reinforcement through cultural and religious tradition, lived experience, political structures, popular entertainments, etc. In other words, we have all been swimming in a fish tank of patriarchy and rape culture for generations, and the social and psychological conditioning created by this dynamic has no doubt been absorbed into every single living person on earth, like exposure to radiation after a bomb.

There are a lot of ways femme-identified people might react to absorbing and living within such a society, and these are reflected in our romance novels. Which is not surprising, because romance novels are about our relationships, which are a central locale for the power of patriarchy in the collective unconscious to come out and play.

Romance novels reflect some common reactions to this dynamic we see in real life:

Romanticizing dominance and possession as love and protection (and more extremely coercion/violence into fantasy)...perhaps to gain a subconscious feeling of greater control and safety.

Internalizing the view that women are physically or emotionally weak, or less deserving of power and dignity and bodily autonomy, and enacting that, either upon themselves or their relationships, or other women, or all three.

Rejecting the dominant narrative and the harm it causes, speaking out, protecting yourself and your loved ones in whatever way you can, and agitating to change the status quo, including in your relationships.

Or--and probably the most common by a mile--you mix and match a little bit of all of these and the million other reactions, because most of us are just doing the best we can with what we have to work with.

WML is a product and mirror of these reactions...and I would propose that is why is it is magnetic and repulsive, polarizing, and so searingly reflective of the world we live in today, even if its politics are firmly and deeply problematic in the context of modern notions of consent, feminism and healthy expressions of love.

This brings up a point from another person in the chat. Which was:

Heather: Also earlier books lack women’s agency in the way we understand it today.

I agree--culture changes rapidly, and our notions of agency, consent, etc evolve with it. I dread the day (and also know with one hundred percent certainty it will come and maybe way earlier than I would hope) when people will look at my books, which I labor over so carefully to imbue with female agency and self-determination, and moan “ugh how regressive and problematic, gross!!”. But the thing is you can never outrun the march of time! Apologies, future readers! I tried!!!

This is not to say we can excuse all problematic content as a marker of the passage of time--sometimes people have really bad intentions!--but it bears mentioning that WML is a reflection of its specific moment in history. (It was written in 1978 and published in 1985.)

Women were navigating the polarizing politics of the feminist/women’s liberation movement and the conservative/“family values” movement. They were being told they should cultivate careers, but also that they were rejecting the traditional Christian role of wife and mother if they did. They were told they should be sexually liberated, but also not to be a “slut” or to put themselves in danger, because getting hurt would be their fault. They faced open sexism, harassment and barriers to success in the workplace. If they didn’t work outside the home, they had to worry about seeming un-ambitious and regressive. And for queer people and people of color, there was a whole separate and malevolent layer of oppression, judgment, violence and bias to contend with. Meanwhile, no matter their identities or careers or personal politics, women were still expected to take on the vast majority of emotional labor and domestic responsibility in their households. And don’t forget they were expected to be groomed and desirable, including having to figure out how to use hairspray, which is a whole separate nightmare.

Are you stressed out just reading this? Are you exhausted? Cuz I sure am. A lot of it we still contend with today, and it is still exhausting, but at least we have done the incremental work of making some of it better, and more out in the open where it can be processed and interrogated.

If all of this was ricocheting in my mind in 1985, and every choice I made seemed to be in some way aligned with a political statement I wasn’t sure I had deliberately made--and amidst all this static I was trying to figure out what *I* wanted and whether I had the privileges to get it or what I might lose in choosing it--I think it might be very relaxing to disappear into a fantasy where everyone just tells me exactly what to do and how to act and I have literally no choice, so as to spare myself this GOD-AWFUL UNWINNABLE MORASS.

Anyway, back to Carole’s original question on this topic: why is Clayton positioned as a hero and Whitney’s falling in love with him despite his violence positioned as an HEA?

Again, I can’t speak for McNaught. But I would speculate the answer is: it was in her head. The same way the weight of these questions is still in all of our heads, and we keep having to inch and claw our way out from under it, screaming.

From Lori: I'm curious about Scarlett's approach to writing consent, and active consent. Does it depend on the character? Do you see the way the characters are seeking/giving consent as a way to learn more about the characters?

It is very important to me that my characters do their sexing consensually, and by that, I mean enthusiastically, vocally, continuously, and in very special moments, in a way that wakes up the whole inn.

I absolutely think how they consent is a function of character and their relationship arc with their partner. When the characters are getting to know each other and each other’s bodies, I put more of an emphasis on how they are communicating and listening for consent--learning each other’s bodies, joys and boundaries.

In the service of this, I sometimes write uncomfortable moments during the course of the growth of the intimacy between the protagonists. To be clear, I don’t mean dubious consent or coercion (let alone assault). I mean moments in which, while consent is freely given, physical or emotional cues are missed or held back during the encounter, and must be grappled with during or after it. Things like shame leading to a behavior that is not fully addressed in the light, moments of not checking in when you should have thought to do so, moments where because of your acculturation or religious beliefs you don’t feel confident expressing your boundaries or desires fully to your partner. In other words, how to negotiate subtleties and talk about sex, in ways that go beyond vocally consenting.

I do this not because I want to valorize misattunements as an example of good, healthy sex--but because I think they are true to life, and something we are still very much reckoning with in the present. By problematizing them, I want to show how strong, honest, trusting sexual communication with active consent and clear boundaries and discussions of tastes and fantasies leads to stronger relationships and better sex. I want to model partners finding the language to say actively and explicitly exactly what they want and how they want it and what their limits are, and how to listen for that and honor it...So that they may keep their fellow patrons at the coaching inn up all night with the volume of their enthusiastic and active consent.

From Andee: What about Georgette Heyer...These Old Shades

Confession time Andee. I have never read a single Georgette Heyer! I have tried but it just never takes. Sorry!

*BONUS From Morgan: Do you have a political project in mind when you are writing? Why or why not?

Yes broadly, but with a varying degree of specificity. On a macro and somewhat highfalutin level, my goal is to use the conventions of historical romance as a trick mirror to explore the continuity between sexual and domestic politics from the past to the present, with a feminist lens. In other words, to see what I can say about the present by recontextualizing modern sexual and romantic anxieties in the era of wigs and chamber pots.

But it is not incidental that I do this with a hefty dose of horny tropes and delicious angst because I am very sincerely writing genre romance novels here, not thinly veiled political treatises.

Sometimes this ends up coming out in more of a diffuse way than in one pointed argument. For example, The Earl I Ruined, is borne out of a melange of musings about outing, public shaming, callout culture, toxic masculinity, paternalism, my annoyance over the fate of Emma in Emma...but also a purely creative desire to write a fizzy second chance honor-marriage fake relationship romance with a spanking fetish and fruit masturbation.

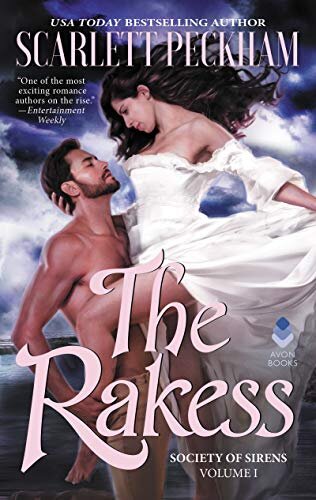

In contrast The Rakess is very obviously and openly driven by “let’s deploy the worst-case-scenario of a female rake trope to punch you in the face with my rage about the alive-and-well horrors of patriarchy and sexual double standards, the trauma and anger and vulnerability they elicit in femme-identified people and/or those with uteruses, and the perils and joys of calling it out and fighting oppression.” The romance arc is secondary, and a way of asserting that this woman society has deemed worthy only of scorn actually deserves every single thing she wants...including compassion and love and torrid rain sex from a sweetheart nurturer jacked Scot who honors her beliefs and values despite his acculturation in patriarchy. Because they both think she is a goddamn hero, fuck you very much.

Thanks for your questions and thanks so much for having me, Morgan and Isabeau! Laters baby!

-Scarlett Peckham

editor’s note: all links were added by us

About the author

From her website…

Scarlett studied English at Columbia University and built a career in communications, but in her free hours always returned to her earliest obsession: those delicious, big-hearted books you devour in the dark and can never bear to put down. Her Golden Heart®-winning debut novel, The Duke I Tempted, was named a Best Romance Novel of 2018 by BookPage and The Washington Post and called “astonishingly good” by The New York Times Book Review.